“and the days rummaging his eyes / and the nights flickering through a slit / of narrow bars. hips. thighs.” – from ‘does Your House have Lions?’ by Sonia Sanchez

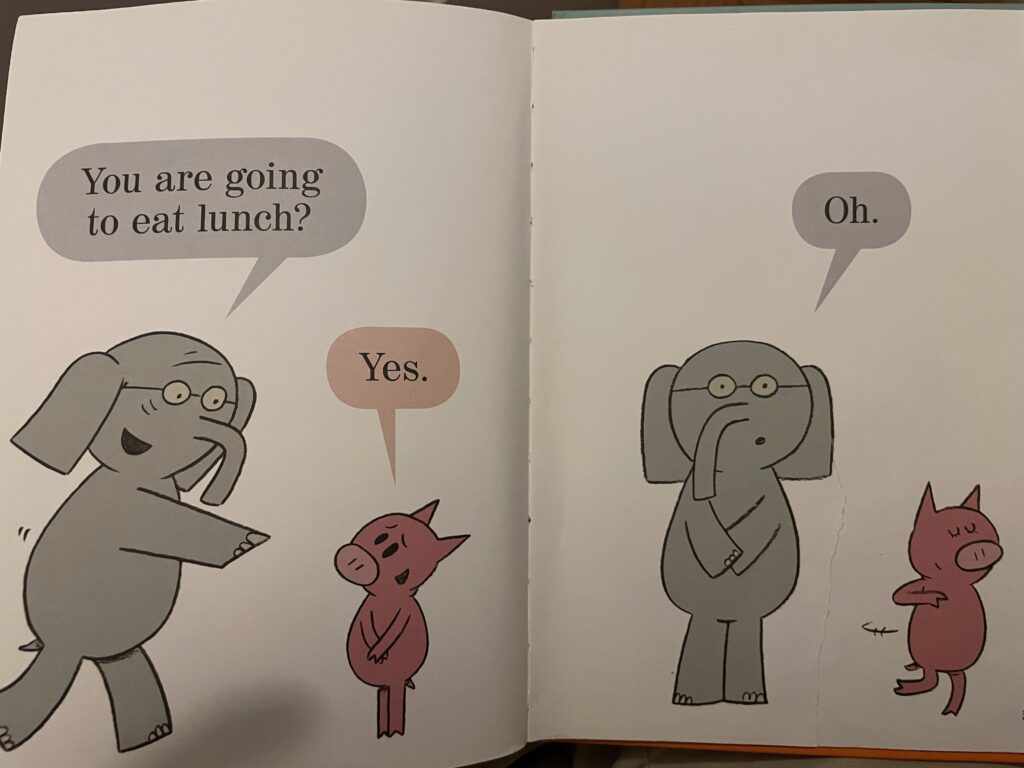

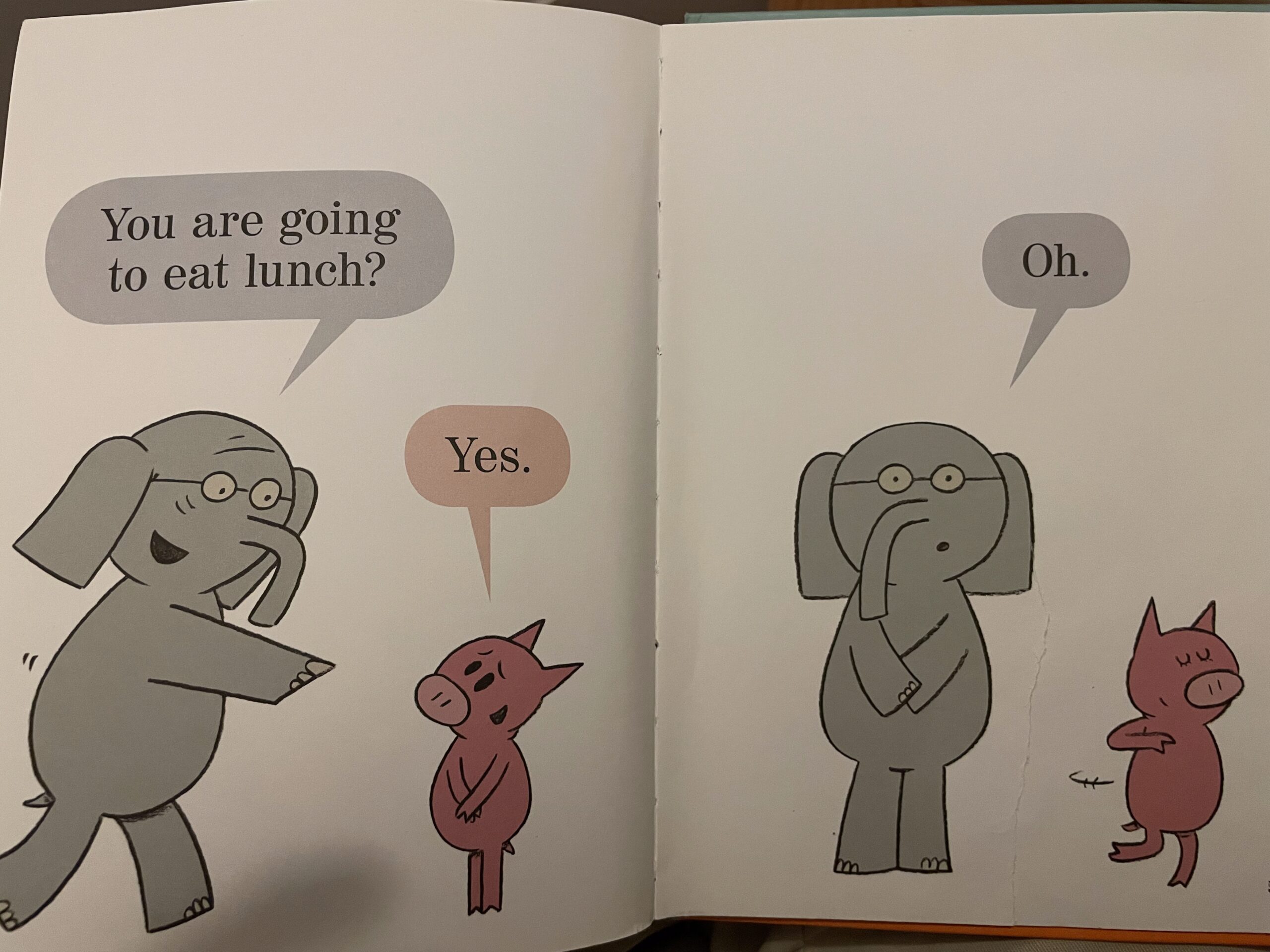

A hallmark of hack column writing is opening with “recently, a person said to me…” but anyway I was putting my kid to bed the other night reading some Gerald & Piggie books you know nothing but the best literature for my child give him some stories that’ll teach him some useful lesson about sharing friends or patience or trying new foods while also priming him for Calvin & Hobbes fandom (we started reading some of those over the summer too) when the child asked me “why don’t Gerald & Piggie books have buildings and trees?”

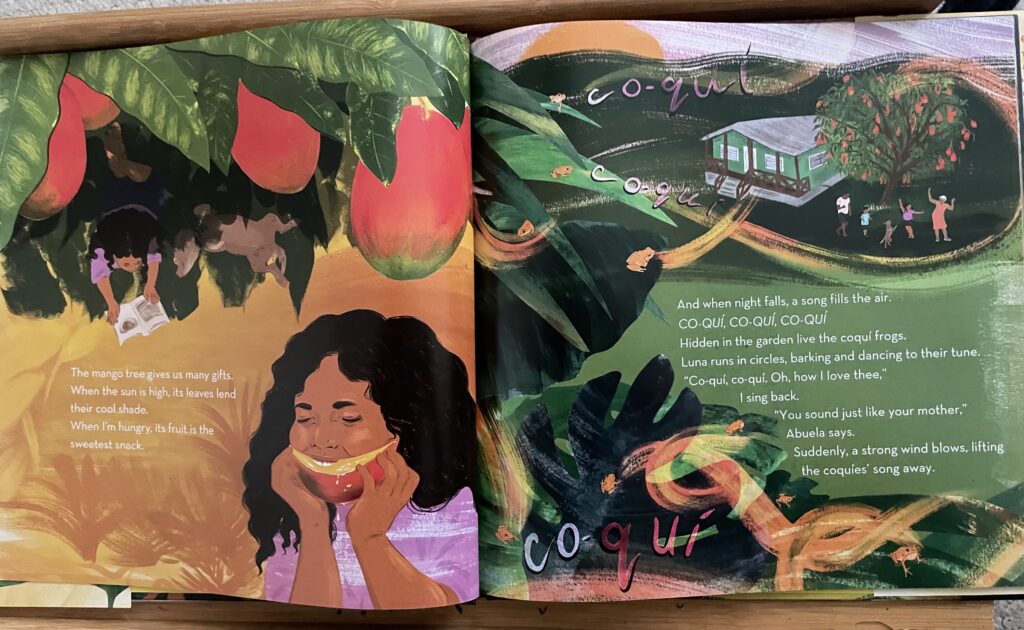

In the interest of journalistic integrity, I don’t remember if he asked about both buildings and trees, or just one. But it’s a useful question, one I wasn’t immediately sure how to answer. Various things that occurred to me after the moment had passed were “think of these books like puppet shows,” “you’re supposed to use your imagination to fill that stuff in,” and “since a pig and an elephant can’t talk and can’t be friends in real life, you’re supposed to imagine how this story would go if it was you and your friends.” I think I settled on “Mo Willems draws in a minimalist style, and you can use your imagination to fill in setting.” Compare Gerald & Piggie to, say, The Coquies Still Sing, a maximalist book about a hurricane destroying a family’s house, but not the frogs. Wall-to-wall color here, plus some illustrations that veer from the observable real world to impressionistic memories and daydreams of the narrator. It’s written by Karina Nicole González and illustrated by Krystal Quiles, and it’s very good, if a little heavy.

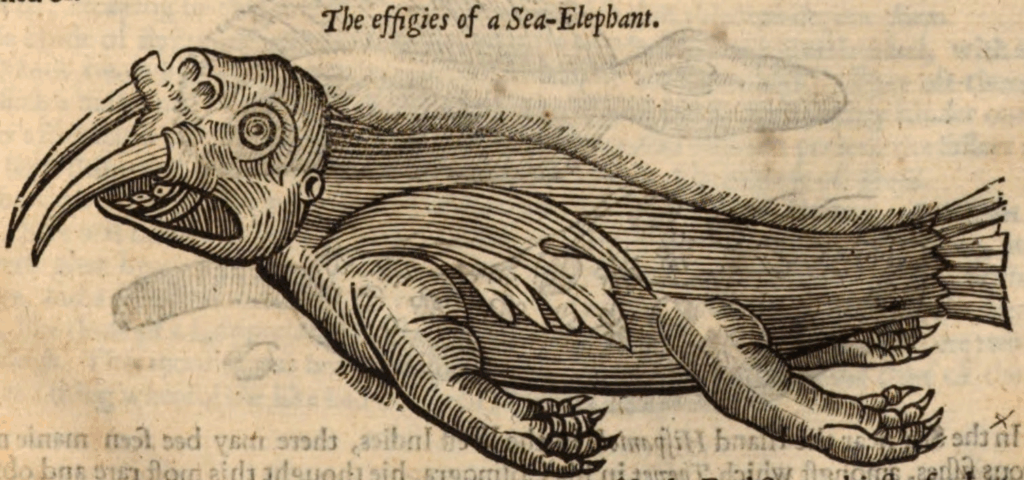

What do you do in your writing? Instinctually, I lean on image. Granular detail can be wondrous, especially in the hands of sensualists like Indra Das or Karen Russell. How about this bit from The Devourers:

We wandered Shahjahanabad always looking behind us, though I found welcome distraction in the many sights I saw. The imperial elephants circling in their sandy arena between the waters of the Yamuna and the walls of the Qila-Mubarak, their pebbled skins made glossy with black paint, trunks brushed with vermillion, tusks clattering in the late-morning air. The parrot-pole on one street, where the nobles took turns in shooting at the bright-green bird tied to the top (it survived all the attempts we saw, whether blessed or because the nobles were drunk or secretly fond of it I cannot say).

That paragraph goes on, and it’s great. What about this one from Swamplandia:

A single note, held in an amber suspension of time, like a charcoal drawing of Icarus falling. It was sad and fierce all at once, alive with a lonely purity. It went on and on, until my own lungs were burning.

“What bird are you calling?” I asked finally, when I couldn’t stand it any longer.

The Bird Man stopped whistling. He grinned, so that I could see all his pebbly teeth.

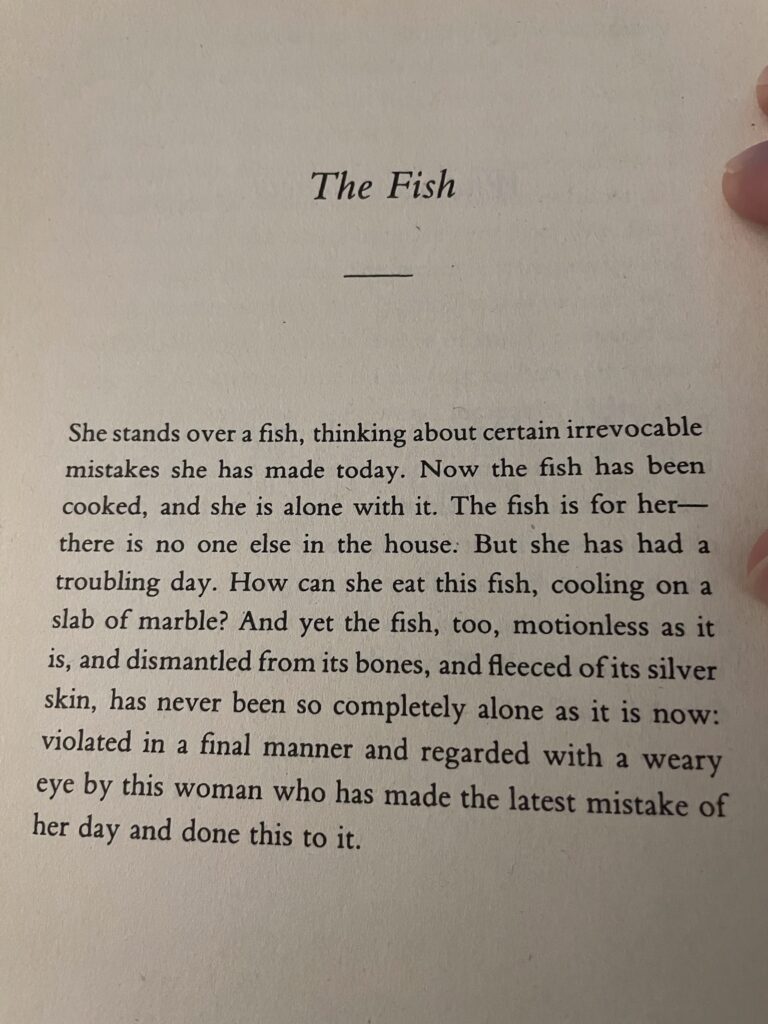

Gorgeous! Compare that to Lydia Davis’s “The Fish,” mine and many others’ go-to example of genius flash fiction. Here it is in its entirety:

That’s a perfect short story. It centers entirely around an image, but it never situates us in a world. We don’t know if the woman lives in Boston, Matazlán, Tokyo, Omaha, or Manchester. We don’t know if she has plants in her kitchen, if she’s listening to music, if there’s a train going by. We don’t know what she does for a living, we don’t know if she enjoys cooking, we don’t even know how she feels about eating. All we know is that this lady fucked up a fish. Much like a child trying to transpose lessons about “hey maybe chill out sometimes instead jumping to the most sky-is-falling-scenario right away,” anyone who has ever cooked before immediately becomes this woman, recounting their many failures and shortcomings in a single instant because of what they did to a fish. I have been that woman many times. Then again, that’s my reading into it, and I am a person who considers themselves to be a good cook who cares deeply enough about food to be anxious most times I serve a meal. I have plenty of friends who only eat because they have to survive. I wonder what they think of this story.

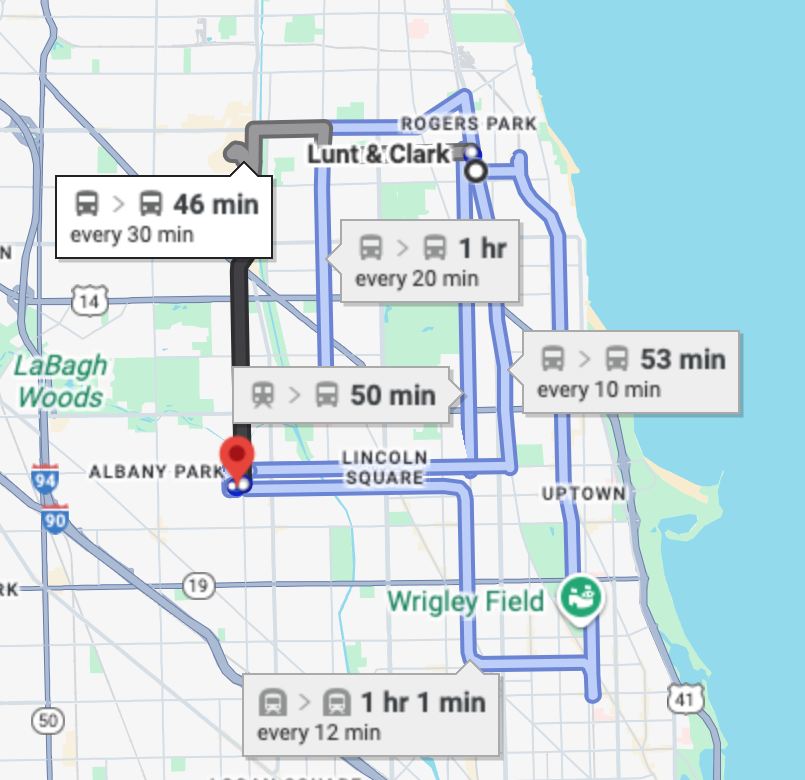

Neither minimalism or maximalism is better than the other. Were I a teacher, I’d assign my students exercises in both styles, then caution them against leaning on one too much. What matters—to me anyway—is some sense of narrative propulsion, along with enough specific detail to make the story feel lived in. Not to spoil the next two Friday Links, here, but I’ve been reading Percival Everett’s James and Theodore C. Van Alst, Jr.‘s The El. It’s not quite right to call Everett a minimalist, but what I’ve read of him is extremely bare bones (particularly Dr. No). Ted, on the other hand, wrote a novel where the whole first act is a group of guys getting from Farwell and Clark to Roosevelt High School via walking and public transportation. One writer doesn’t put in a lot of trees (despite writing The Trees), one writer puts in every tree (or garage door tagged with 70s gang signs, whichever). Yet both writers write novels I can’t put down.

My favorite writer, Aimee Bender, is honestly my favorite writer because of how well she navigates this stylistic tightrope. She isn’t exclusively a flash fiction writer, she has written both long and short novels, she can basically do no wrong, in my objective opinion. Sometimes the stories and sentences are long, sometimes they are short, but there is always both narrative propulsion and a sensuous, specific, detailed account of both place and subjective experience. Here are some examples:

“I’m alone at the party and I have my drink in a mug because by the time I got here, at the ideal moment of lateness, the host had used all her bluish gasses with fluted stems that she bought from the local home-supply store that all others within a ten-block radius had bought too because at some inexplicable point in time, everybody woke up with identical taste.” (from “Off”)

“There was a ten in my wallet between four ones and I lifted them all out. I had another drippy bite of mango.” (from “Fruit and Words”)

“Her heart pulled its curtain as she held each potato up to the bare hanging lightbulb and looked at its hint of neck, its almost torso, its small backside.” (from “Dearth”)

“My genes, my love, are rubber bands and rope; make yourself a structure you can live inside.” (from “Hymn”)

And that’s completely contextless! Imagine how good those lines are while you’re reading the story!

Where does this leave poetry? As always, in the toughest spot. I want poems that have movement and an overwhelming amount of detail, and I want the poems to be shorter than flash fiction. Every poem I write is an attempt to fit the whole of Lake Michigan and the streets of Chicago into eight lines. I don’t have a book out.

So I ask again: does your writing have buildings and trees? If you want to get writing, here’s a prompt: try to write a Gerald & Piggie book. That’s 57 pages of entirely talking heads, with conflicts and adventures and resolutions. Then, try to write a two-page paragraph describing the room you’re currently in, and nothing else. Mash the two together. See what happens.

Sorry you got an email,

Chris

After reading this post, I find it so strange that you aren’t a teacher!

me too tbh! Life, uh, found a way for that not to be the case. Think that’s why I blog and podcast now.