“White people often spent time admiring their survival of one thing or another.” – Percival Everett, ‘James’

To read a Percival Everett book is to read a book with all of the nonsense taken out. That’s not to call his prose minimalist, or lifeless, or voiceless. On a recent blog, Daniel O’Brien called Everett’s work “only the good parts.” I agree. Also, I read a book of his poetry this week. Everyone wants to go read Huck Finn after they read James. I just want more Percival Everett.

What I’ve Been Reading This Week:

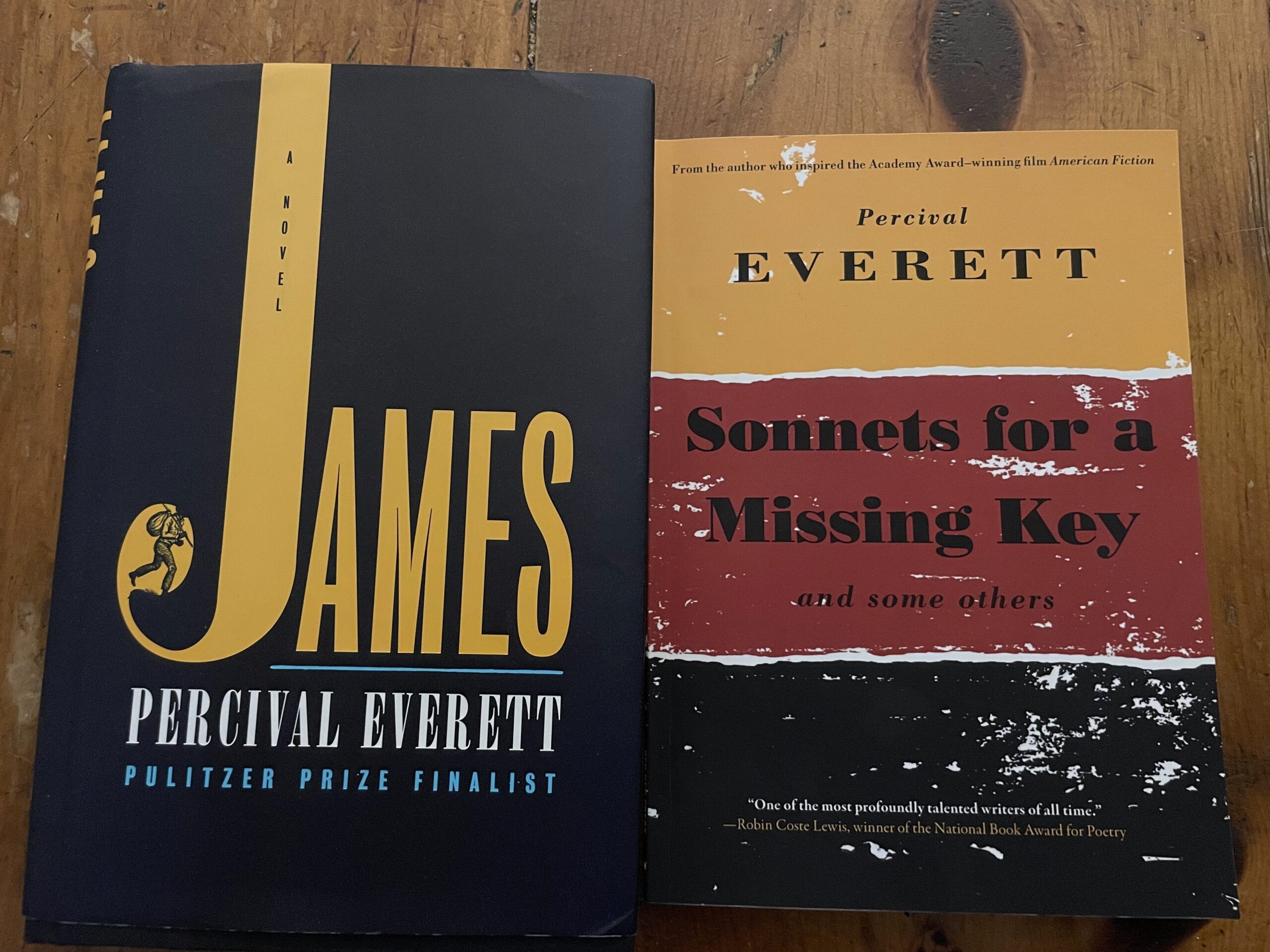

Two books that, in lesser hands, would’ve been totally uninteresting. One is a re-telling of a centuries-old classic, which is a genre that can be wonderful or unbearable, depending. The other is a book of formal poems inspired by piano players. That, too, can be delightful or drudgery, depending. Fortunately, we are in the capable hands of Percival Everett, maybe the most That Dude writer out there right now. I read James and Sonnets For A Missing Key and some others.

James by Percival Everett: every time I read a Percival Everett book, I have to wonder if it’s the best novel ever written. I still think the answer is 100 Years Of Solitude, for the record, and I do think doing a Bill Simmons-style pyramid ranking of every book I’ve ever read is an immature and foolish endeavor. Sounds fun, tho, and I’ll probably do it one day.

You probably know that this novel is a re-telling of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but from Jim’s perspective. For that reason alone, you should read it—we are in the midst of a cultural course correction on the antebellum south (and its subsequent backlash). The story of the 2010s to me will always be a decade where people quit being shy about talking about racism, a decade where we got some great scholarly stuff like The 1619 Project and Four Hundred Souls, we got public intellectuals like Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jamelle Bouie and Eve L. Ewing and Michelle Alexander making names for themselves, we got the BLM movement, and we quit putting up with rose-tinted nonsense about the antebellum south. Fuck Gone With The Wind, burn Gone With The Wind next time you have a fire going, and don’t think twice. Anyway, this book neither shies away from nor lingers on the horrors that come with slavery. That’s a skill Everett has: depicting things frankly, without sentimentality, and letting absurdity hang in the air without a wink or a nudge. The result, in this particular case, is a story that takes place in the 1860s, but feels pretty immediate—that immediacy coming from the fact that the story of the 2020s is going to be white backlash to the 2010s, and people at the levers of power have been openly pro-slavery before. What would you do if you and your friend were confronted by an aggressive slaver in a barn? What would you do if you and your friend were confronted by a cop? By an ICE agent?

More importantly for James, our cunning narrator: how do you react when a member of the underclass acts in a way that upsets your expectations?

Whenever a book blows up without any of the obvious trappings of “this will appeal to latte liberal NYT readers” or “this is will get on Oprah’s book club,” I always wonder why. What about this particular book made people decide to take time out of their busy lives and read it? There’s a Marxist reading here. Questions about who can compel whom to labor, and for whom. Questions about what happens when the underclass begins refusing to be a underclass. The ending, much like the ending of The Trees, makes you think about what needs to happen to remake contemporary society—not just The Big Spectacle of the scene, but also the very last lines of this novel. The implications of them.

Sonnets For A Missing Key and some others by Percival Everett: not to spoil Tuesday, but Bob and I talked about a poem from this book on a recording of The Line Break this week. Both Bob and my good friend Han VanderHart (talking off-mic) expressed surprise that Everett had a book of poems, to which I said, “same, that’s why I bought this.” Collections of poems by writers primarily known as fiction writers carries some risk—I like Stuart Dybek’s poetry, for example, but am kinda bored by Raymond Carver’s (love his fiction, of course). Fortunately, Percival Everett is one a them good writers. These poems are deceptively simple, propulsive in their movement while lulling you into the rhythm of the form (half the book is sonnets). The back calls to us: “inspired by the Preludes of Chopin and the piano solos of Art Tatum, these experimental sonnets seek to question timbre and tone. That’s bullshit. They are just sonnets.” I read this book in roughly an hour, lounging in bed on a Sunday morning with Mallory and the kid. I hadn’t even put my contacts in yet. It was pleasant, but I immediately wanted to re-read, more slowly this time. To let these poems sail by like a thin seed pod in a light breeze would be a mistake. There’s so much depth here, there is so much mingling of the abstract and the hyper-specific. The leaps and poem logic are dazzling, like, did this dude really just begin a poem with “A sad and great evil is among us,” and then follow that line with “lapping at water we have poured for the dogs.” Yes. Yes he did. Read this book, and sit with it—though for different reasons I’d tell you to sit with, say, The Trees or James.

Is Percival Everett the greatest living writer? I can’t stand such conversations. But he absolutely has some sort of title belt, and has since at least 2020, if not longer.

LINKS!

- Sinners Celebrates the Decadent Intimacy of the Black South by Evette Dionne in The Flytrap

- Trump is terrified of Black culture. But not for reasons you think by Saida Grundy in The Guardian

- upfromsumdirt’s Abstract Africana by upfromsumdirt in Hayden’s Ferry Review

- Radical Change Isn’t Free by Ed Pilkington in The Guardian. Subhed: “The Black Panthers shook America awake before the party was eviscerated by the US government. Their children paid a steep price, but also emerged with unassailable pride and burning lessons for today”

- “Realness” by Anaïs Duplan in ANMLY

What’re you still doing here? Don’t you know that Micah and Brendan have a show?

If you work in the service industry, may you clean up in tips this weekend. Remember, as James did, that you are you, and no one can take that away from you. Sure, maybe sometimes you steal a canoe or lie to some white people or [REDACTED SPOILER], but it’s worth it. Whatever this metaphor means for you: don’t let people call you Jim. You are James.

Sorry you got an email,

Chris